Camp Century Long Read

Reflections on the past, the future, and the value immersive technology can bring

Part One: Camp Century - Our History and Our Future

At the height of the Cold War, the Arctic became an unlikely battleground. The United States had fallen behind in its ability to operate in cold environments. Given that polar travel was the possible vector of a Soviet assault against NATO countries, they felt the need to rectify this gap in their operational knowledge.

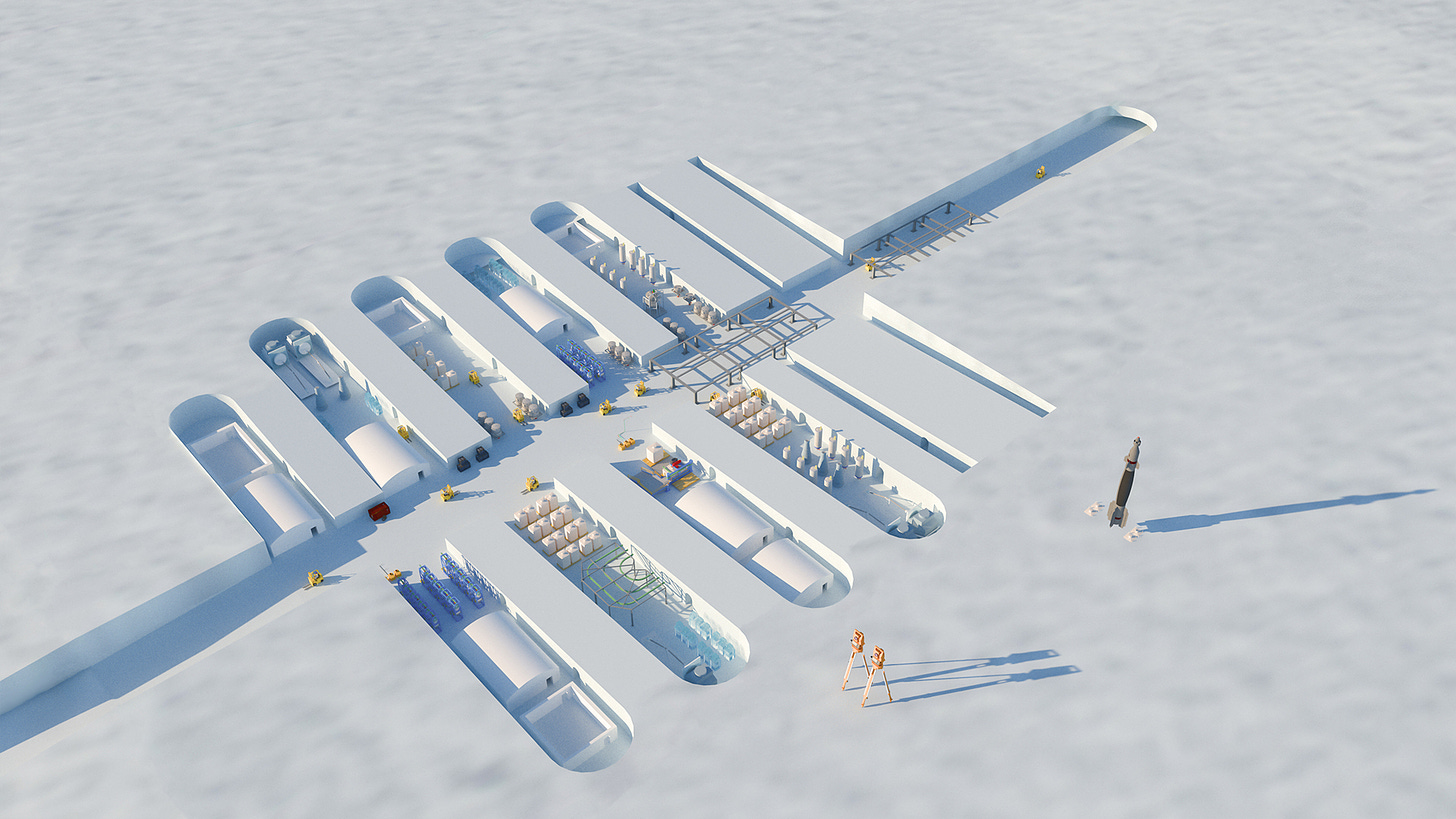

We at Studio ANRK have been working on a meticulously reconstructed version of Camp Century using Unreal Engine for several years now. The project initially premiered as a virtual tour at IDFA in 2021, and Copenhagen Film Festival as part of CPH:DOX. We worked closely with Nicole Paglia (writer), and Emeka Malbert (3d creator) and were joined by some of our collaborators, including former Camp Century resident, Søren Gregerson; Research Climatologist, William Colgan; Local resident, Navarana Sørensen; and Kristian Nielsen, co-author of 'The Cold War Under the Ice Sheet of Greenland.'

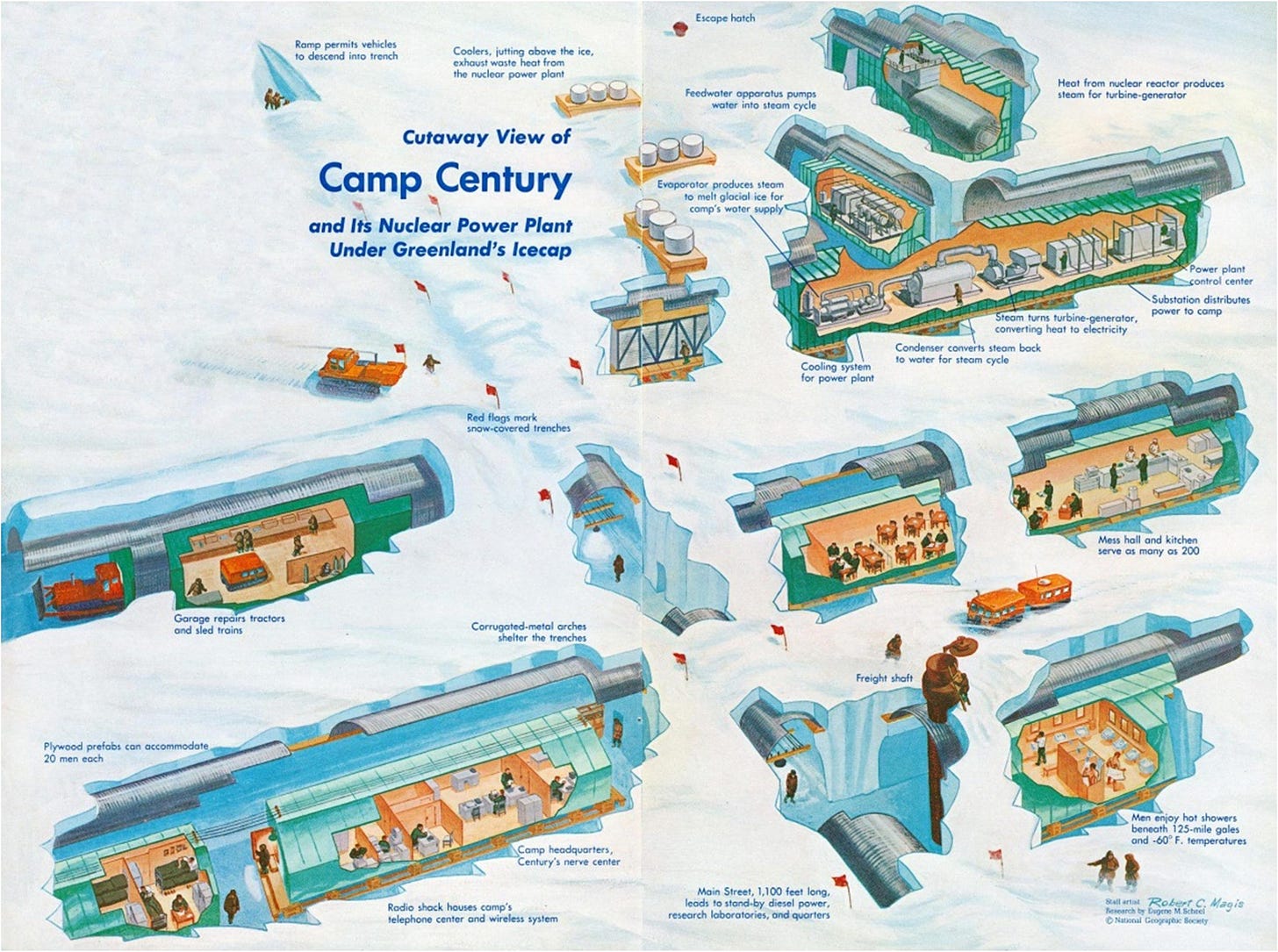

In 1958, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was tasked with constructing a remote base underground, and providing defence and supplies for an allied scientific research effort. Using over six thousand tons of supplies, they built Camp Century in Greenland, about one hundred and fifty miles east of Thule Air Base on the Western coast.

Camp Century was not a purely military endeavour, the scientific research conducted by the Polar Research and Development Program during the eight years of operation was valuable, and remains relevant to this day. Camp Century is a milestone in climatological and geological terms, it was the first time a core sample was taken out from the arctic ice, providing climate data going back 10,000 years. This taught us more about climate modelling than any prior experiment. And the lessons learned about day to day life in inhospitable environments, white out storms, as well as ionospheric data remain incredibly valuable.

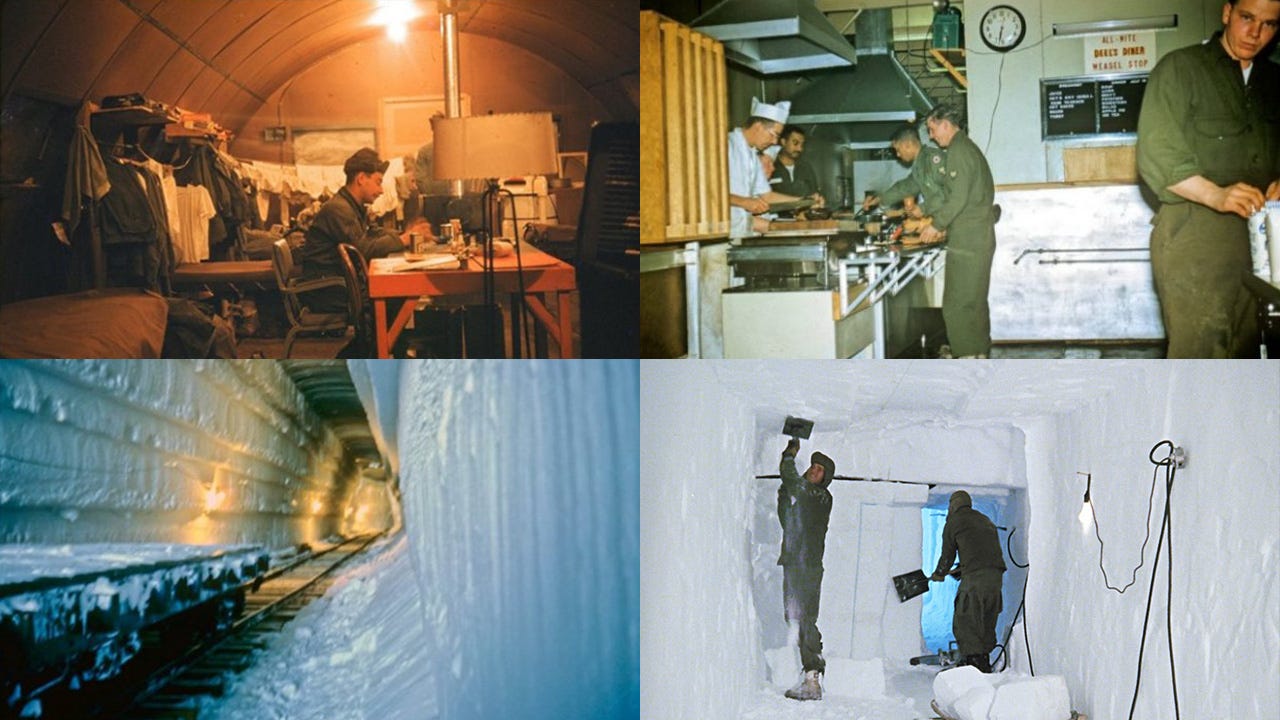

It was publicly promoted as a victory over the elements, and a symbol of futuristic cities built in inhospitable places. The camp’s layout resembled that of a small town below the ice, with a ‘Main Street’ from where you could visit the chaplaincy, a barber shop, a cinema room, a canteen and of course sleeping and living quarters.

But Camp Century was also part of a darker plan, not surprising considering the Cold War tensions of the time. It was part of Project Iceworm, a secret military effort to build a network of nuclear missile silos placed under the Arctic ice.

The weaponization of the Arctic was abandoned a decade later, it became increasingly evident that the ice shelf around Camp Century was much more volatile below the surface than was expected - Inuit people call inland ice ‘slow water’, the ice wasn’t stable enough to maintain the structure of Camp Century, walls and spaces needed constant rebuilding or they’d collapse.

Part Two: Camp Century - What Remains?

On one hand, all we have left of Camp Century is recordings. There are a few military documentaries, many scientific papers, and the photographic and blueprint evidence that have been retained over the decades. Perhaps an occasional memento, keepsake, or museum piece exists, scattered over four different continents. Everything else has been rendered useless, swallowed by ice, snow, and time.

And yet, the habitation of Camp Century left a permanent mark on the planet. As global warming eats away at the ice sheets at the poles, it’s quite possible that the skeleton that was Camp Century will once again see the light. When that happens, it will very likely release biological, chemical, and radioactive waste that was thought to be ‘permanently’ interred in the frosty wastes. A combined 115,000 gallons of diesel fuel, sewage, and radioactive coolant will be dumped into the environment, unless it’s removed beforehand.

The old maxim of ‘leave nothing behind but your shadow’ becomes more impossible as the climate being explored becomes more extreme. In order to power the 3km worth of under-ice corridors, the US army brought in a portable, medium-sized nuclear reactor, a first of its kind, to fuel the entire base. In their portability and modularity, these small nuclear reactors suddenly presented the possibility for the first time of bringing immense amounts of power to the most remote parts of the world, inciting a moment of hope and optimism for where nuclear power would propel humans.

And yet, Camp Century’s greatest legacy was the ice core records that were extracted in 1966, described as the ‘jewel in the Camp Century crown’. In the summer of 1966, after multiple attempts over the course of 5 years with various thermal and mechanical drills, they were able to successfully pull out a 1400m long ice core. By analysing the entrapped gasses, isotopes, pollen and dust all the way down the core they could reveal a climate record that dated back as far as 10,000 years, a unique and remarkable engineering and scientific achievement that still provides a rich data legacy for climate scientists today.

Part Three: Camp Century and Space

As much as the Moon landing was a Cold War public relations project, Camp Century was a secretive display of military know-how; a reaction to something that NATO felt the Soviet Union was better prepared for.

Camp Century aimed to construct a nuclear-powered research centre and missile launch site, all under the guise of scientific research. Specifically, its goal was to assess the feasibility of deploying ballistic missiles within the ice sheet. During this era the other intense geopolitical competition between the United States and the Soviet Union, besides nuclear advancement, was the international Space Race.

While Project Camp Century had a military and strategic focus, the concurrent projects explorations of inhospitable environments were fuelled by broader aspirations for technological and scientific breakthroughs. In this historical context, both projects symbolized not only the rivalry of the era but also the strides in innovation and scientific discovery that characterised the Cold War era.

Human exploration of extreme environments is a precursor to one of the greatest challenges facing our species: The habitation of other worlds, climates and planets. Camp Century presents an obvious analogy with space flight: being confined in small spaces, long periods away from home, harsh climates, not to mention it is essentially laid out like a spaceship would be.

Diving deeper, there are vital lessons we can learn and apply to future plans for human space exploration from Camp Century. Missions to Mars, initially to explore and later to inhabit, will encounter many of the same problems.

The Psychology of Confinement

Travel to the red planet will be an introduction to the kind of isolation experienced by those who underwent the rigours of Arctic living. The crew count to Mars will likely be even smaller, leading to increased psychological stress and more incidents of interpersonal strain as the months roll by.

Camp Century engineer, Ray Hansen recalls in a blog that ‘mental problems were not new to Site 2. Ed Clark told about how, in 1955 I think, one of the guys out there radioed TUTO [name of the base camp] describing trees growing on the icecap.’

The psychological strain, often referred to as polar madness, of living underground with a group of 150 people, all of whom were also men is evident. Typical symptoms were “fatigue, headaches, gastrointestinal problems, sleeping difficulties, impaired cognition such as a state of spontaneous fugue also called “the Antarctic stare”, depressed mood, or tension towards crew members”.

And It was not only the mental strain of inhabiting such a strange place, but also that of returning as a stranger .

‘I left Greenland in the spring and went back to Ft. Monmouth. I was a total stranger there, having been gone all winter’, Bob Mitchell recounts in his memories of Camp Century.

It is a strikingly similar experience to that of Kate Greene, a journalist who lived inside a geodesic dome with 5 other people for 4 months, simulating confinement on Mars. Greene writes ‘When an astronaut comes back, Earth isn’t where it was...You leave and come back, and home isn’t what it was.’ Greene also describes tense a living situation at times and communication difficulties that led to eruptive arguments.

Having both enough and good quality social encounters is clearly a key factor defining the success of any community, let alone an off world one. Living in a small closed community you are free to define your own cultures, your ways of communication and social etiquettes but in such close proximity, conflicts are explosive and a lack of communication builds interpersonal strain over time, as the breakdown of many of the commune experiments in the 60’s and 70’s teach us. We can innovate the most high-tech and hospitable Martian homes, but if the quality of our human connections are lacking this will all be of secondary importance.

Learning non-violent ways of communicating is a skill that very few of us have been taught, but would go far in building thriving communities, both on earth and off it. Will it be included in the Mars curriculum is the question.

Sustainable Infrastructure and Systems

More people mean more resources are required. How does that impact the number of interplanetary trips required to make the mission a success?

Possibly the biggest lesson we can learn is that the supply model used at Camp Century isn’t feasible for off-world projects. The resources used in a single space launch are (pardon the pun) astronomical when compared to the mass that can actually be shipped. This problem multiplies as the Mars community grows. When their population increased, Camp Century simply increased the number of supply runs, increased the consumption of temporary resources, and leaving behind a bigger and bigger waste footprint. These are not options when settling another planet.

Now we know that local, sustainable survival methods need to be established as soon as possible when creating a base in an inhospitable world. This means solar power arrays need to be constructed in order to complement the nuclear reactor. It means sourcing fresh water locally is of primary concern, and in fact is the number one challenge to any Mars mission. It means constructing controlled greenhouses to supplement and eventually replace food shipments. And it means designing an aggressive recycling program.

Some of the building techniques used at Camp Century could certainly carry over to extra-planetary settlement. For example, using natural materials as heat insulation and as radiation barriers. Modular underground living, much like building within the ice trenches dug into the Arctic, is a viable way to avoid radiation and storm dangers. After building frames and shells from biological polymers or local ceramics, they could be placed in trenches and covered with natural Martian soil. Habitats could be connected via underground tunnels, with strategic escape hatches to the surface implemented every so often. This was the exact strategy used at Camp Century.

Since the time of Camp Century, it’s been discovered that any nuclear waste produced by power generation is actually a potential source of additional power. Certain generation four fast reactors use a sustainable closed fuel cycle, meaning their ‘waste’ breeds fuel for another part of the energy production cycle. This was unavailable in the 50’s and 60’s, but demonstrably solves some of the issues that Camp Century faced as far as long term nuclear power use.

Camp Century was amongst the first to implement a portable nuclear reactor in the early 60’s, however by the mid 70’s many were already being decommissioned after their relatively short operating lives, low efficiency, and high radioactivity levels. But the vision for Small Modular Reactor (SMR’s) that are portable has been revived in recent years amongst environmentalists arguing for them ‘as a cornerstone of clean-energy policies meant to address climate change’ and it seems no coincidence that these have sprung up around the same time as designing for interplanetary living. In the same way that SMR’s marked an era of off-grid exploration in the 60’s, their recent resurgence may also allude to the fact that there is a new curiosity in air, a sense of flightiness to find out what else is possible. Do SMR’s tell us something about our current state of hope and optimism for the future?

Ethical Considerations

In many ways, Camp Century provides lessons in what not to do. When they abandoned the camp in 1968, thinking that it would be encased in ice forever, they didn’t consider much what that forever really meant. Herein the irony of Camp Century is revealed, and an indicator towards the fact that climate science wasn’t Camp Century’s main motivator, because, while the data legacy of Camp Century has helped provide a baseline for future climate research, it also left behind a ticking environmental timebomb in the form of dormant biological, chemical, and radioactive waste, a clean up job that no one has claimed responsibility for yet. Predictions calculate that the hazardous waste will be exposed by 2090, but even this could be much sooner depending on the uncertain melt rates in coming years.

The story of Camp Century is far from over, and whether it is a success story or a disaster will depend on how we respond to what is left of the camp and more generally to the changing climate in the decades to come. As we wait to see how this story unfolds, maybe it is the perfect moment to reflect on what we bring and what we leave behind to these environments when we attempt to colonise them with science and human expansion.

The indigenous Greenlandic communities around Camp Century are still processing and making amends with the fact that more than 100 Inugguit villagers were forced to leave with only a few days notice to make way for the base operations, while preparing to be worst affected by the impending nuclear waste problem that will thaw into rivers and surrounding oceans in the coming decades.

‘We will probably never get over that they used this area as an American Base’ says Navarana Sorensen, a native Greenlander.

If extra-planetary settlement is upon us, reflecting on past expeditions like Camp Century is an important step in ensuring that we don’t make the same mistakes again.

Being There Without Being There

From the Camp Century experience, we know that habitation is incredibly dangerous and cost-prohibitive. But we also know that entire bases can be constructed in virtual reality for a fraction of that cost.

A large part of adapting to Martian life will be adapting the body and the psyche to new routines and habits, new rituals around food and socializing and this is not always a smooth transition, as outlined in Kate Greene’s recount of a 4-month occupation inside a Mars simulator. There will be teething problems but simulation spaces, such as the one described in the article, could help foresee and investigate the symptoms of this transition sickness in order to better prepare for them.

Remote automation is the step in between. Our experiences with the Mars Rovers have taught us a lot about remote command and control of automated devices on other planets. Once significant local resources are identified, we can ship the correct kinds of robotic aids from Earth. Then, all of the initial construction can take place on Mars, and be experienced in virtual reality on Earth. Those in charge of the project can place trenches, design habitats, and create infrastructure in the virtual world, which the robots will make a reality on the surface of the red planet. Techniques such as manual digging and drilling, 3D printing, materials sifting and processing, and laser powder bed fusion can all be used to replicate the virtual construction as Martian reality.

We’ve already started such work with autonomous undersea vehicles right here on Earth. The first offshore diverless remote hyperbaric tie-in operation was completed in 2019. More specialized diverless rigs are being developed for a multitude of undersea construction tasks. As that technology is perfected, it can be applied to space habitation as well.

We’re still many years off, but the power of virtual reality to act as a medium for building entire projects in extreme environments is much closer than any of us might have imagined just twenty years ago.

Part Four: Visiting Camp Century Today

Buried 36 meters below ground, an in-person visit to Camp Century is a current impossibility. Not only is Arctic exploration prohibitively expensive, but there would be no way to reach the remains of the camp without a massive heavy digging project and the clean-up of the aforementioned waste.

And yet, people can still visit it... virtually.

We, at Studio ANRK, have been working on a virtual reality version of Camp Century for over 5 years now, in collaboration with Nicole Paglia and Paradiddle Pictures. After extensive research, studying every scrap of surviving footage, and with photographic and blueprint resources as a reference, we slowly built a copy of Camp Century. We continue to interview people to understand what each of the spaces were like, and how it felt living there.

Camp Century VR was built as a social experience, meaning you can tour the camp with others. Whether that's a friend, or a stranger you bump into - it's a place where multiple people can meet, talk, and walk together as they explore the camp’s tunnels, living and common areas, laboratories, and military command chambers.

The early social-VR prototype tour offers you the opportunity to explore the military secrecy, the important scientific work, the positive environmental impacts of the ice core studies, the negative environmental impacts of the waste left behind, the displacement of people from their home, and who is responsible for the future clean-up of the site when it all resurfaces.

Being able to immerse oneself in a place that required special clearance, within the depths of one of the least hospitable environments on the planet, is a unique experience to say the least.

But more important than the thrill, and arguably more important than the historical aspects of the Cold War that necessitated such an extreme venture, are the lessons learned. And how we can apply those lessons to the next challenges that face the human race.

Alongside the VR experience, we're developing a real-time film, combining reconstruction assets with traditional documentary techniques.

Our goal for Camp Century was always to create a traditional film, with the unique ability to explore Camp Century in full colour and high visual detail. Using UE5 cinematic camera work, this is now possible.

The magic with UE5 and virtual camera control, is it gives us the ability to create camera sequences that look like they were filmed in the real Camp Century. What would be exciting for us, would be to add actors to these scenes and create a traditional documentary using Virtual Production techniques. The point being, you can’t film in Camp Century today and very little footage remains of it. Working with archive footage gives us a glimpse of what it would have been like, allowing us to recreate a completely realistic, accurate recreation of Camp Century as a film set, for the purposes of a documentary.

Part Five: Camp Century - Conclusion

Camp Century is a tale of humans attempting to conquer extreme environments and in many ways succeeding, but ultimately being chased out by the unreckonable forces of nature. The most destructive weapon mankind has ever invented, the nuclear missile that Camp Century attempted to store in its tunnels, was no match for the immense weight of the melting ice sheets.

While people have been living on top of the Greenland ice cap for centuries, Camp Century was the first large-scale operation to put humans below it. Perhaps scale was the problem, but it was precisely in its scale that Camp Century proved unsustainable as a long term solution. It was left behind as quickly as it arrived, and while no doubt a remarkable feat, what does success really entail? This becomes an important question for us to answer as we consider the realities of interplanetary settlement.

Moving forwards it will not be enough to conquer. Victory over nature cannot be our goal. The planet cannot sustain such conflict any longer. Even though Camp Century was born of the Cold War, we must shed the language of militancy that convinces us that we exist in competition with nature. Our relationship to the earth needs healing and to do this we must practice humility, surrendering sometimes, as the inhabitants of Camp Century did, to the unnegotiable will of nature. We must realize that the pace of real change is sometimes slower than we would like it to be.

The faithful recreation of the camp in virtual reality was a massive undertaking. But it allowed a kind of portal to be created. We can now step into a forbidden place of an era long past. A place that wouldn’t even exist without a unique kind of political tension; one that we thought was a thing of the past, but that could very well be re-emerging in the modern age.

The invitation to explore Camp Century is there, right at the fingertips of anyone with the curiosity and passion required to step into a new reality. Though the experience of Arctic exploration and habitation might be virtual, the lessons we can learn are very much real.

You can track the progress we make with Camp Century next year by bookmarking studioanrk.com/campcentury, and if you enjoyed this long read please do let us know and forward it to anyone who may enjoy reading it.

Team ANRK